Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi arriving at the Kuala Lumpur High Court, October 5, 2021. — Picture by Miera Zulyana

KUALA LUMPUR, Oct 6 — Funds in charitable foundation Yayasan Akalbudi and purported charitable donations totalling millions in ringgit from businessmen were ultimately intended for Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi’s benefit under his alleged money laundering scheme, instead of for charity, the prosecution argued in the High Court today.

Deputy public prosecutor Harris Ong Mohd Jeffery Ong today argued the objective factual circumstances as a whole would show that Ahmad Zahid was involved in money laundering activities.

In this trial, Ahmad Zahid is facing 27 money-laundering charges relating to funds that were allegedly proceeds from unlawful activities, including 25 charges involving his alleged instructions to law firm Lewis & Co on 25 separate occasions to put over RM53 million into fixed deposit accounts.

The 26th charge is over Ahmad Zahid’s alleged instructions to buy two bungalows worth RM5.9 million via a cheque from Lewis & Co involving unlawful funds, while the 27th charge involves his alleged instructions to moneychanger Omar Ali Abdullah to convert RM7.5 million of illegal funds into 35 cheques that were then given to the same law firm to be placed in fixed deposits.

Harris had stressed that all the funds mentioned in Ahmad Zahid’s trial — whether from alleged bribes, alleged criminal breach of trust in the channelling of money from charitable foundation Yayasan Akalbudi where Ahmad Zahid is a trustee, alleged illegal funds–had ultimately ended up in law firm Lewis & Co’s client account.

Ahmad Zahid’s lawyers had previously argued Lewis & Co is a trustee that held funds in a client account on trust for Yayasan Akalbudi, which is a foundation aimed at eradicating poverty.

But Harris today suggested that the funds in Lewis & Co ultimately were not used for charity, but became part of a money laundering scheme where the money was placed in fixed deposits and ultimately left available for Ahmad Zahid to use for purposes such as the RM5.9 million purchase of two bungalows and for a share purchase deal that was later aborted.

How does a money laundering process look like?

Today, Harris cited Martyn J Bridges’ legal research paper “Money laundering methodology” to explain a typical money laundering process and key elements, as well as how it could apply to the facts in Ahmad Zahid’s case to show that money laundering had taken place.

Among other things, Harris highlighted how Bridges had described money laundering to be a complex process with no easy formula to identify a money launderer or money laundering scheme.

Harris also noted Bridges had highlighted the three common features of money laundering techniques, namely the need to maintain control of the funds, the need to transform the structure and form of the funds, and the need to hide the true ownership and origin of the funds.

For example, Harris noted the “secretive” money laundering technique allegedly used in this case, where Ahmad Zahid had allegedly given mere verbal instructions to Lewis & Co’s partner Muralidharan Balan Pillai and moneychanger Omar Ali on the handling of millions of ringgit.

“Why secretive? Because the instructions are given directly, orally, whether it is to Omar Ali or to Muralidharan, the two important witnesses in the money laundering case. Because why, there is no written instruction, no written appointment for Muralidharan, for Lewis & Co, and for Omar Ali, to receive large amounts of cash money,” he said.

Harris claimed that all three features of money laundering techniques were shown in this case, arguing that Ahmad Zahid had maintained control of the funds as he had instructed the law firm in the issuing of a RM8.6 million cheque for the purchase of shares in a company (with the money later returned after the deal fell through) and in the purchase of two bungalows in Country Heights, Kajang, Selangor for a total RM5.9 million. (The RM8.6 million cheque had come from Yayasan Akalbudi’s RM17.9 million cheque to Lewis & Co, with the entire sum ultimately used for fixed deposits after the RM8.6 million was refunded.)

Harris also said the funds’ structure was transformed, such as when Omar Ali converted bags of cash totalling RM7.5 million that unknown individuals handed to him into cheques before making them payable to Lewis & Co’s client account, with Omar Ali having obtained such cheques from unrelated customers and friends by offering them cash for loan or currency exchange in return for the cheques.

Harris also said alleged bribes in the form of businessmen’s cheques worth millions of ringgit were transformed from cheques into cash upon being deposited into Lewis & Co’s client account, and that these funds later were further transformed when used to buy fixed deposits in banks.

Harris also suggested the feature of concealing the unlawful funds’ true ownership and origin was also present in Ahmad Zahid’s case through the transformation of cheques into fixed deposits after entering Lewis & Co’s client account, while further highlighting Omar Ali’s cash-to-cheques conversion as being aimed at structuring transactions to avoid mandatory reporting procedures as he could have alternatively just deposited the cash directly for the alleged intended charitable foundation or their alleged trustee law firm Lewis & Co.

“He took almost two months to convert RM7.5 million into 35 cheques, without any proper documentation, just acting purely on trust, Yang Arif. The trust from the accused,” Harris said when explaining the lengths that Omar Ali took for the cash-to-cheques conversion including even asking his staff on one instance to convert some cash into cheques.

Omar Ali Abdullah is pictured at the Kuala Lumpur High Court June 18, 2020. — Picture by Shafwan Zaidon

The role of client accounts and the accused

Among other things, Harris highlighted the intergovernmental anti-money laundering organisation Financial Action Task Force’s observation — as cited in Bridges’ paper — of the high levels of complicity by lawyers in money laundering with the use of lawyers’ client accounts in complex structured transactions.

He also noted Bridges’ research as having found that money launderers were exploiting or using money changers for money laundering activities, as well as concern that alleged “professional launderers” or those in the legal profession or accountants were not doing enough to fight money laundering or to report suspicious transactions.

“The use of trustee or client account is a serious problem not only in Malaysia but also globally, Yang Arif,” he said, when noting that all 27 money laundering charges that Ahmad Zahid is facing involves either money that went into or out of law firm Lewis & Co’s client account.

While acknowledging that it could not be immediately said whether the cash received by Omar Ali was illegal or not, Harris said all the evidence however would lead to the conclusion that all the processes involved in the handling of funds, in this case, are all actions relating to money laundering.

“For example, the role played by Lewis & Co, the role and function played by Omar Ali, and the role and function also by all the so-called donors, philanthropists,” he said, urging the High Court to give a maximum evaluation on the purpose of such transactions as well as the method used to deliver the money.

Harris said the High Court should also consider that Ahmad Zahid as the accused had not done anything to check the source of the funds, noting that he did not for example ask Omar Ali why the moneychanger had converted the cash received into cheques.

“All the evidence must be read together to show the elements of crime of money laundering involving the accused in this case,” he said, also pointing at the large amount of money involved in this case and how these funds were moved around.

While High Court judge Datuk Collin Lawrence Sequerah noted the prosecution would have to show whether the source of cash given to Omar Ali was illegal, Harris instead referred to the entire process and method in handling the cash money — the cash-to-cheques conversion and its destination of the Lewis & Co’s client account — to decide whether these were illegal funds since the source could not be proven.

With all the alleged bribes and alleged criminal breach of trust funds ending up in the same law firm Lewis & Co’s client account, Harris noted that people could nowadays easily launder funds by putting it in a client account or with a trustee, but went on to say that how the funds were used shows that it was for Ahmad Zahid’s benefit.

“But in the end, luckily for prosecution, we have evidence, the purchase of shares, purchase of bungalows, what happened to fixed deposits, there is no element of charity, but for own benefit of the accused,” he said, referring to Ahmad Zahid as the accused.

“All the circumstances, all the facts and evidence, pointing to one conclusion — the involvement of the accused in all the transactions.

“This is the spirit of money laundering Act, to show that the accused was involved directly or indirectly in transactions. We are talking about transactions, we are not talking about the origin of money,” he said.

Previously, Omar Ali said Ahmad Zahid had told him that the unknown individuals who handed the cash were from Yayasan Albukhary.

(The prosecution had argued that investigations show that Yayasan Albukhary did not donate in such a way, while Ahmad Zahid’s lawyers said this had not been proven. The judge had previously meanwhile asked why the alleged donation from Yayasan Albukhary to Yayasan Akalbudi was not done directly through a cheque but through cash.)

Today, Harris contrasted Yayasan Albukhary as having a proper website with proper information on how it was established and a proper account, as compared to Yayasan Akalbudi.

“But what do we have until now, with regards to Yayasan Akalbudi? They managed to show the building of mosque, tahfiz school, but unfortunately for Mubarak Hussain and Mastoro Kenny, all cheques supposedly for mosque and tahfiz ended up for purchase of bungalows,” he said, referring to how RM7 million in donations from two businessmen for charitable and religious purposes were later placed in fixed deposits via Lewis & Co before the fixed deposit funds were withdrawn to pay RM5.9 million for the two bungalows.

He said all this goes to show the “complexity” of money laundering in this case, where the origins of some funds cannot be determined but the way how the money was manipulated and moved around to the client’s account and to buy shares and property could be shown.

He said Ahmad Zahid did not give proper written instructions to the law firm or assurance about the cheques delivered to them, and that he had only verbally said the funds are charity money and asked the law firm to place them in the client account.

Harris concluded by saying that the prosecution has shown credible evidence to prove all elements of the 27 money laundering charges against Ahmad Zahid, and argued that the High Court should call Ahmad Zahid to enter his defence in order to explain himself and all his actions in relation to the 27 offences.

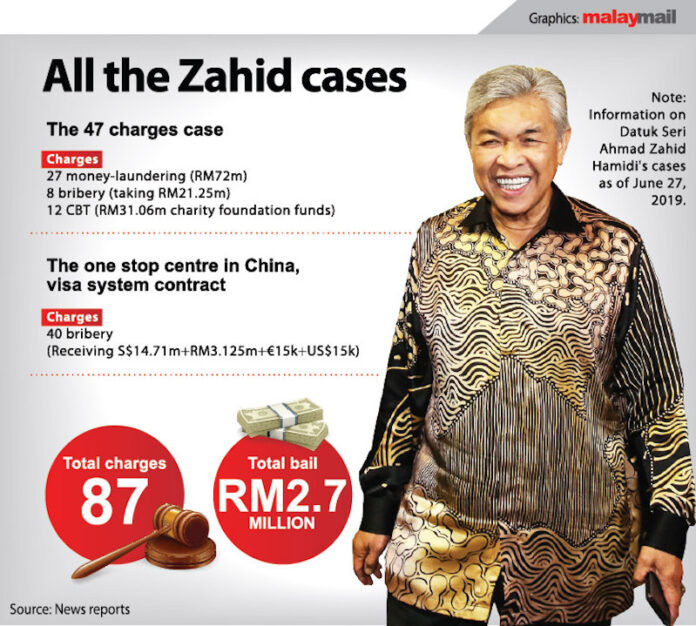

In this trial, Ahmad Zahid — who is a former home minister and currently Umno president — is facing 47 charges, namely 12 counts of criminal breach of trust in relation to charitable foundation Yayasan Akalbudi’s funds, 27 counts of money laundering, and eight counts of bribery charges.

The trial resumes next Monday.