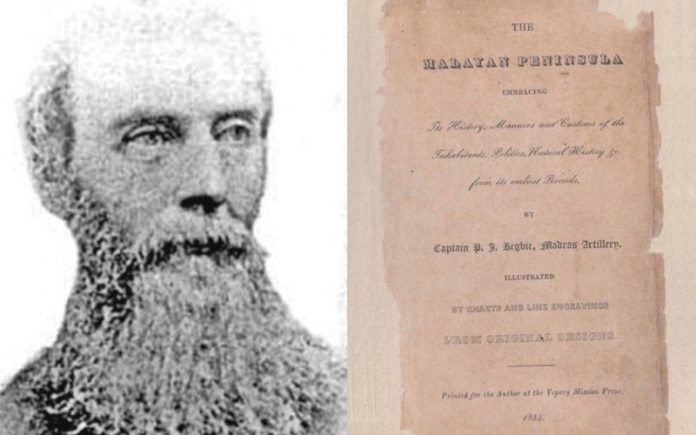

Peter James Begbie (1804-1864) was a Captain in the East India Company’s Madras Artillery and was serving in Malacca when he published ‘The Malayan Peninsula’ in 1834 with the subtitle ‘Its History, Manners and Customs of the Inhabitants, Politics, Natural History &c. from its earliest Records’.

This was an ambitious and scholarly work, stretching to over 500 pages, and was the first attempt in the English language to provide an encyclopaedic description of Malaya.

Although most of the book’s contents are hopelessly out of date, it does contain some interesting historical details for the modern reader, which might otherwise have gone unrecorded.

During research on the backgrounds of some of the headstones in the old Dutch graveyard in Melaka, a grave belonging to Frances Ann Begbie, aged 5, who died on Aug 23, 1832, caught my eye. She turned out to be the eldest of Peter James Begbie’s 10 children, thus bringing his book to my attention.

Begbie was an accomplished linguist and could translate several European languages, including Dutch, which enabled him to tap Dutch sources for his research.

His book contained a number of illustrations which Begbie appears to have made himself and a number of these are reproduced here (copyright status: public domain).

Here are a few examples of the type of information contained in the book.

Begbie listed the principal Malayan states of the peninsula as Kedah, Perak, Salengor (Selangor), Malacca, Johol, Sungei Ujong, Rumbow (Johol, Sungai Ujong and Rembau are now part of Negeri Sembilan), Johor, including Pahang and Packanja (possibly Pekan?), Tringano (Terengganu), Callantan (Kelantan), and Patani (now part of Thailand).

Some of the language used reflected colonialist attitudes of the day, which to the modern audience would sound patronising, racist or insulting – such as his description of the Semang people (orang asli) that need not be reprinted here.

But on the other hand, he took the trouble to research their lifestyle and customs in considerable detail and even included a glossary of Semang words.

He related the history of the Portuguese conquest and occupation of Malacca at some length but was dismissive about the Portuguese community he found there, saying “The descendants of the conquerors of Malacca have, with hardly any exception, sunk into a state of deep poverty and ignorance.”

Begbie’s sketch, The Ruined Gate of the Old Fort, which is now more commonly called Port de Santiago or A Famosa, appears to show that there were additional sections of the wall still standing in 1834, to the left and right of the gate. These sections have been demolished.

In addition to recording his own observations, Begbie sought out authoritative sources such as Tuanku Putri, the stepmother of the Sultan of Johore, who provided Begbie with an in-depth genealogy of the Johore Rajahs.

Three chapters of the book are given over to the Nanning War, a relatively minor scrap, in which Begbie took part. Nanning was a district of Malacca that was not going to accept British rule and taxes without a fight.

The rebellion, led by Datuk Dol Said, was eventually quelled but not without casualties on the British side, some of whom are buried in the Dutch Graveyard and one in Alor Gajah.

He wrote about the Anglo-Chinese College, whose foundation stone was laid in 1818 by Major-General William Farquhar, Resident of Malacca.

The college was established under the guidance of Protestant missionary Robert Morrison. Begbie’s fifth child was named William Morrison Begbie, perhaps in honour of the great man?

Begbie also described the Chinese tombs at Bukit Cina in Malacca. He revealed that “on the top of one of these [hills at Bukit Cina] are the remains of an ancient Dutch redoubt.”

Do any traces of that fort remain today? He may have been referring to the fort on St John’s Hill, about 800m away from Bukit Cina, though.

Commenting on the superstitious beliefs of the Malay seamen about auspicious days for nautical expeditions, Begbie included a chart (from Johore) detailing the days and months of the year with symbols denoting the likely weather conditions for each day.

There are a lot of statistical tables in the book, such as this breakdown of Singapore’s population by race in 1832 and 1833, showing that the Chinese were the largest community even in the early days of Singapore, though overwhelmingly male.

Other chapters describe Penang, Singapore, Junk Ceylon (modern-day Phuket), tin mining, natural history and religious beliefs. The book is most comprehensive, and it is a wonder Begbie had any time for his soldiering and other work.

However, Begbie did not remain in Malacca for long. He returned to India and continued to serve until his retirement in 1857 when he was made Honorary Major-General.

This article first appeared in Malaysia Traveller.